Excavaciones del Karum de Kanish (Kultepe,Capadocia,Turquía)

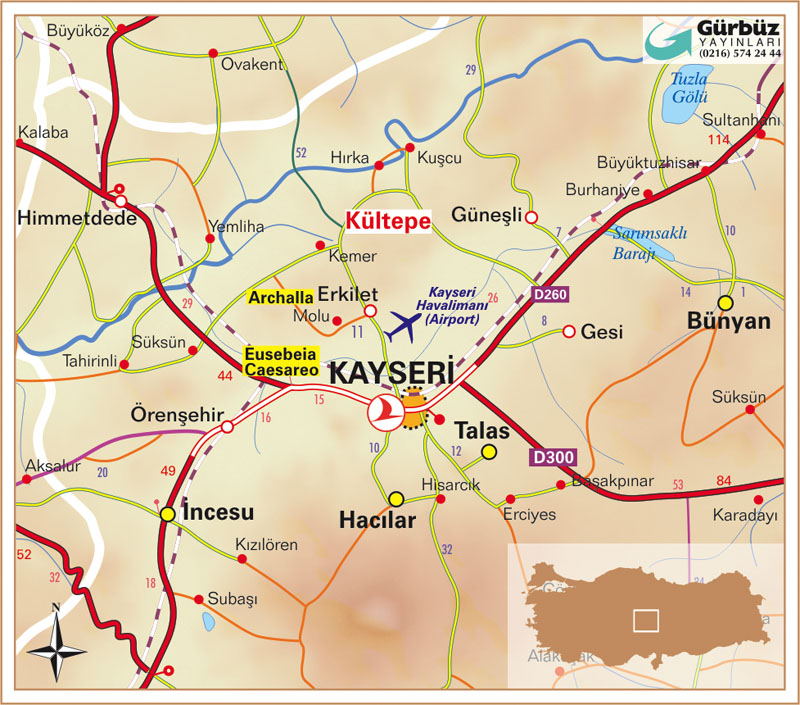

Kültepe ( 38°51′N 35°38′E / 38.85, 35.633) es el nombre de una antigua ciudad en Anatolia central, Turquía, antes llamada Kanes, Kanesh o Kârum de Kanesh en asirio, que significaba “la colonia mercantil ( asiria) de Kanes” (escrito como Karum Kaniş en turco moderno), y posiblemente Nesa en hitita.

38°51′N 35°38′E / 38.85, 35.633) es el nombre de una antigua ciudad en Anatolia central, Turquía, antes llamada Kanes, Kanesh o Kârum de Kanesh en asirio, que significaba “la colonia mercantil ( asiria) de Kanes” (escrito como Karum Kaniş en turco moderno), y posiblemente Nesa en hitita.

La ciudad moderna más cercana a Kültepe es Kayseri, a 20 en dirección suroeste.

Excavaciones en el karum de Kanish,Turquia

Excavaciones en el karum de Kanish,Turquia

Kültepe es una moderna ciudad próxima a la antigua ciudad de Kaneš (Kanesh; posiblemente la hitita Neša), localizada en la provincia turca de Kayseri, en Anatolia Central. La ciudad moderna más cercana es Kayseri, a unos 20 km al sudoeste.

http://www.turkishairlines.com/images/skylife/11-2005/35/6_351.jpg

Kaneš, inhabited continuously from the Chalcolithic period down to Roman times, flourished most strongly as an important merchant colony (kârum) of the Old Assyrian kingdom, from ca. 20th to 16th centuries BC. A late (c 1400 BC) witness to an old tradition includes a king of Kaneš called Zipani among seventeen local city-kings who rose up against the Akkadian Naram-Sin (ruled c.2254-2218).[1] It is the site of discovery of the earliest traces of the Hittite language, and the earliest attestation of any Indo-European language, dated to the 20th century BC. The native term for the Hittite language was nešili “[language] of Neša” o “nesita”.

Kültepe was excavated by the late Professor Tahsin Özgüç from 1948 until his death in 2005.

- Level IV-III. Little excavation has been done for these levels, which represent the site’s first habitation. No writing is attested, and archaeologists assume that both levels’ inhabitants were illiterate.

- Level II, 1974 BC - 1836 BC (Mesopotamian Middle Chronology according to Veenhof). Craftsmen of this time and place specialised in earthen drinking vessels in the shape of animals, often for religious rituals. During this period, Assyrian merchants established themselves in a merchant colony (kârum) attached to the city, which was by now called “Kaneš”. Bullae of Naram-Sin of Eshnunna have been found toward the end of this level (Ozkan 1993). This level was burned to the ground.

- Level Ib, 1798 BC - 1740 BC. After an interval of abandonment, the city was rebuilt over the ruins of the old, and again became a prosperous trade center. This trade was under the control of Ishme-Dagan, who was put in control of Assur when his father, Shamshi-Adad I conquered Ekallatum and Assur. However, the colony was again destroyed by fire.

- Level Ia. The city was reinhabited, but the Assyrian colony was no longer inhabited. The culture was early Hittite. Its name in Hittite became “Kaneša”, but was more commonly contracted to “Neša”.

Some attribute Level II’s burning to the conquest of the city of Assur by the kings of Eshnunna; but Bryce blames it on the raid of Uhna. Some attribute Level Ib’s burning to the fall of Assur to other nearby kings and eventually to Hammurabi of Babylon.

Kârum of Kaneš

El karum de Kanesh o Kanish visto desde el aire, asentamiento de una colonia de mercaderes asirios del Reino Antiguo.

The quarter of the city of most interest to historians is the Kârum of Kaneš, “merchant-colony city of Kaneš” in Assyrian. During the Bronze Age in this region, the Kârum was a portion of the city set aside by local officials for the early Assyrian merchants to use without paying taxes, as long as the goods remained inside the kârum. The term kârum means “port” in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the time, although it was extended to refer to any trading colony whether it bordered water or not.

Several other cities in Anatolia also had kârum, but the largest was Kaneš. This important kârum was inhabited by soldiers and merchants from Assyria for hundreds of years, who traded local tin and wool for luxury items, foodstuffs and spices, and, woven fabrics from the Assyrian homeland and from Elam.

The remains of the kârum form a large circular mound 500m in diameter and about 20m above the plain (a Tell). The kârum settlement site is the result of several superposed stratigraphic periods. New buildings were constructed on top of the remains of the earlier periods, thus there is a deep stratigraphy from prehistoric times to the early Hittite period.

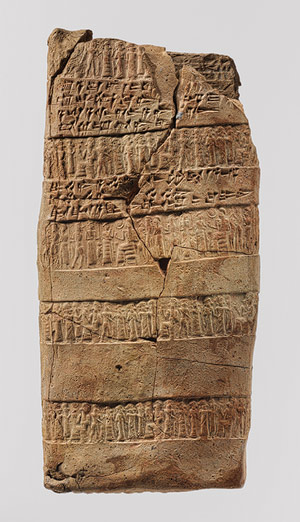

Kanesh case tablet , tablilla capadocia del Karum de Kanish dentro de un “sobre” sellado con un cilindro-sello.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/66.245.5b

Caly, L. 6 5/8 in. (16.8 cm) Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J.J. Klejman, 1966 (66.245.5b), Cuneiform tablet case, 1920–1840 b.c.; Old Assyrian Trading Colony period

Central Anatolia, Kültepe (Karum Kanesh)

Clay,

The kârum was destroyed by fire at the end of both levels II and Ib. The inhabitants left most of their possessions behind to be found by modern archaeologists.

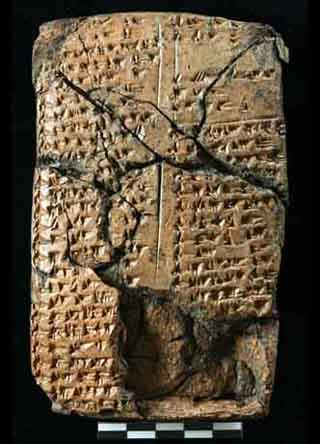

The findings have included enormous numbers of baked clay tablets, some that were enclosed in clay envelopes stamped using cylinder seals. The documents record common activities such as trade and legal arrangements. They record trade between the Assyrian colony and the city-state of Assur, as well as trade between Assyrian merchants and local people. The trade was run by families, not by the state of Assyria. These Kültepe texts are the oldest written documents from Anatolia. Although they are written in Old Assyrian, the Hittite loanwords and names in these texts are the oldest record of any Indo-European language (see also Ishara). Most of the archaeological evidence found is typical of Anatolia rather than Assyria, but the use of cuneiform writing as well as the dialect are the best indications of Assyrian presence.

Assyrian business letter on clay tablet from Kanesh Cappadocia 1800-1750

“Around 20,000 clay tablets were found at the site of Kültepe (ancient Kanesh). Such a large find indicates that the city had an extensive commercial quarter, where foreign Assyrian merchants lived and operated during the 19th century BC. Sent from Itur-ili in Assyria to Ennam-Ashur in Kanesh, this letter concerns the important trade in precious metals. Itur-ili, the senior partner, offers wise words of advice to Ennam-Ashur: “This is important; no dishonest man must cheat you! So do not succumb to drink!”" - Walters Art Museum

Photographed at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mharrsch/sets/34519/with/4129726518/

Kaneša

The king of Zalpuwa, Uhna, raided Kanes; after which the Zalpuwans carried off the city’s “Sius” idol. The king of Kussara, Pithana, conquered Level Ia Neša “in the night, by force”; but “did not do evil to anyone in it”.

Neša revolted against the rule of Pithana’s son Anitta, but Anitta quashed the revolt and made Neša his capital. Anitta further invaded Zalpuwa, took its king Huzziya captive, and recovered the Sius idol for Neša.[2]

In the 17th century BC, Anitta’s descendents moved their capital to Hattusa (which Anitta had cursed); thus founding the line of Hittite kings. These people named their language Nešili, i.e. “the language of Neša”.

Dating of the Waršama Sarayi

At Level II, the destruction was so total that no wood survived for dendrochronological studies. In 2003, researchers from Cornell University dated wood in Level Ib from the rest of the city (which was built centuries earlier). The dendrochronologists dated the bulk of the wood from buildings of the Waršama Sarayi to 1832 BCE, with further refurbishments up to 1779 BCE.[3]

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Trevor Bryce, The Kingdom of the Hittites, rev, ed, 2005:10

En español: Vázquez Hoys, Ana Mª-- -

-

|

HISTORIA ANTIGUA UNIVERSAL.Próximo Oriente y Egipto. Autor: VAZQUEZ HOYS ANA MARIA

Editorial: SANZ Y TORRES Carrera: HISTORIA (PLAN NUEVO y GRADO ) Asignatura: HISTORIA ANTIGUA UNIVERSAL Curso: PRIMER CURSO,TRONCAL Tipo: TEXTOS BÁSICOS

Edición: 2ª - 2007 Edición Páginas: 701 páginas. ISBN: 9788496808126 Tamaño: 29×22 Idioma: ESPAÑOL |

|||

http://www.uned.es/geo-1-historia-antigua-universal/ASIRIA/Reino_Antiguo.htm

En las fuentes históricas de Babilonia, el territorio septentrional colindante es llamado Subartu. Ya en sus orígenes se considera un reino de estirpe semita amorita, aunque la población debía de ser mixta, presemita subartea(ROSA) y semita (VERDE). EL FUNDADOR DEL REINO ASIRIO El fundador de la primera dinastía parece ser un tal Puzurassur, aunque sus orígenes y la historia de sus sucesores se pierde en crónicas legendarias redactadas en una época muy tardía. Aparentemente, el tejido habitacional en aldeas dispersas se vio alterado por la presencia de poblaciones trashumantes que actúan como intermediarias en intercambios comerciales de mediano alcance que pronto se extendió hasta Anatolia. La intervención del comercio en la configuración política de Asiria es perceptible en la disparidad funcional de sus principales centros, Assur como sede de la actividad comercial, y Nínive, centro regulador de la actividad agrícola del entorno. La historia fáctica bajo los primeros reyes se nos escapa por la escasez de la información, pero pronto debió de ser una potencia equiparable a las del sur. Su auge está íntimamente relacionado con la renta obtenida de las cargas impuestas a las actividades comerciales, de manera que el monarca da más la imagen de gran agente comercial que de rey absoluto. LAS AGENCIAS DE COMERCIO ASIRIAS:KARUM Ya en el último tercio del siglo XIX, los asirios instalan en Anatolia agencias de comercio, karum, consideradas como colonias. En efecto, en los alrededores de la ciudad de Kanish (Kültepe) en Capadocia, los comerciantes particulares asirios habitaban un "karum", donde se ha descubierto una valiosísima colección de millares de tablillas que permite a los investigadores reconstruir su funcionamiento. El "karum" de Kanish es una agencia comercial asiria, que funciona con una organización política propia al margen de la ciudad indígena contigua, con la que no obstante firman pactos e incluso obtienen protección militar de ella. Se trata, pues, de un lugar central estable que controla una red de agencias menores (wabaratu) diseminadas por Anatolia. Su objetivo es la exportación de bienes manufacturados (tejidos) y estaño, a cambio de los cuales obtiene cobre, plata y oro. Para su correcto funcionamiento desarrollan los más sofisticados sistemas crediticios y de tasación conocidos hasta entonces. Los beneficios repercutían sobre las empresas privadas pertenecientes a las grandes familias de Assur que tenían sus agentes en los distintos "karu". Estas, a su vez, contribuyen mediante imposiciones tributarias al erario público, dando lugar así a uno de los más sólidos ingresos para el estado asirio. El máximo beneficiario de este sistema es naturalmente el monarca, que posee además las atribuciones propias de los reyes de la época; pero en el caso asirio se da otra circunstancia especial, pues la propia ciudad está representada a través de una asamblea, a la que pertenecen todos los ciudadanos libres, con capacidad para tornar decisiones. Tal vez sea, como en el caso del reino hitita o en el período formativo de los reinos meridionales, expresión de unas formas más colectivas de decisión política, propias de comunidades de pequeño tamaño y no excesivamente jerarquizadas. Pero la organización cívica estaba representada también por un magistrado electivo y temporal, (limum), presidente de la asamblea de ciudadanos, en el ayuntamiento o Bit Alim, "casa de los epónimos," lo que pone de manifiesto la originalidad institucional asiria. A finales del siglo XIX se produce un brusco cambio en toda esta situación, cuando el "karum" de Kanish es destruido, no se sabe bien en qué circunstancias. Al parecer, la propia capital del reino sufre graves alteraciones y poco después ve cómo accede al trono un amorreo, miembro de aquellas tribus que previamente se habían dejado sentir por la zona septentrional de Siria y que también habían conseguido instalar una dinastía propia en Babilonia, a la que corresponde Hammurabi. Con el nuevo rey, Shamshiadad (1812-1780 ) , la ciudad de Assur pierde parte de su protagonismo, pues el centro de gravedad del reino se desplaza hacia la zona del alto Khabur, donde erige el palacio de Shubat-Enlil (Tell Leilan).

Shubat-Enlil (Tell Leilan

Harvey Weiss et al., The genesis and collapse of Third Millennium north Mesopotamian Civilization, Science, vol. 291, pp. 995-1088, 1993

H. M. Cullen, Climate change and the collapse of the Akkadian empire: Evidence from the deep sea, Geology, vol. 28, pp. 379-382

M. Staubwasser and H. Weiss, Holocene Climate and Cultural Evolution in Late Prehistoric-Early Historic West Asia,” in M. Staubwasser and H. Weiss, eds., Holocene Climate and Cultural Evolution in Late Prehistoric-Early Historic West Asia. Quaternary Research (special issue) Volume 66, Issue 3 (November), pp. 372-387

Ristvet, L. and H. Weiss 2005 “The Hābūr Region in the Late Third and Early Second Millennium B.C.,” in Winfried Orthmann, ed., The History and Archaeology of Syria. Vol. 1. Saabrucken: Saarbrucken Verlag

Harvey Weiss, Tell Leilan and Shubat Enlil, Mari, Annales de Recherches Interdisciplinaires, vol. 4, pp. 269-92, 1985

Harvey Weiss, Excavations at Tell Leilan and the Origins of North Mesopotamian cities in the Third Millennium B.C., Paléorient, vol 9, iss. 2, pp. 39-52, 1983

Harvey Weiss et al., 1985 Excavations at Tell Leilan, Syria, American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 529-581, 1990

Jesper Eidem, Lauren Ristvet and Harvey Weiss, The Royal Archives from Tell Leilan: Old Babylonian Letters and Treaties from the Eastern Lower Town Palace, Yale University Press, 2010, ISBN-10 0300165455

References

- The Climate of Man — II: The curse of Akkad. Elizabeth Kolbert. The New Yorker. May 2, 2005.

- Marc van de Mieroop: The Mesopotamian City. Oxford University Press 1999. ISBN 0-19-815286-8

- Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz, The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC), Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-79666-0

- Weiss, Harvey, Francesca deLillis, Dominique deMoulins, Jesper Eidem, Thomas Guilderson, Ulla Kasten, Torben Larsen, Lucia Mori, Lauren Ristvet, Elena Rova, and Wilma Wetterstrom, 2002, Revising the contours of history at Tell Leilan. Annales Archeologiques Arabes Syriennes, Cinquantenaire. Damascus.

- 000000000000000000000000000000000

Una carta de la ciudad de Mari dice:

“La ciudad de Shubat Enlil es una fortaleza, fundada en el corazón del territorio...”, para garantizar las comunicaciones entre Mesopotamia y Anatolia.

Las campañas militares de Shamshiadad tuvieron precisamente como finalidad asegurar la fluidez del tráfico comercial en su propio beneficio y en tal sentido se debe entender la toma de Mari; aunque por otro lado, buscaba la consolidación de las zonas fronterizas.

Sus éxitos militares hicieron de Asiria la máxima potencia de su época y el propio monarca se preocupó por dar un aparato administrativo más eficaz a su reino. Esa pudiera ser la correcta interpretación de la apertura a las influencias meridionales, que afectan tanto al sistema organizativo, como al ámbito religioso, fenómeno al que no es ajeno el propio exilio de Shamshiadad en Babilonia antes de convertirse en monarca de un estado territorial.

Al frente de las ciudades sometidas, como Mari, sitúa a sus propios hijos o personas de confianza, protegidos por guarniciones militares. Para las campañas militares las tropas estacionadas son auxiliadas por levas extraordinarias entre la población productora que es desmovilizada al término de las mismas. Así pues, el antiguo reino asirio se fundamenta en el consabido equilibrio inestable entre la explotación de los recursos agrícolas, la actividad comercial, la presión tributaria sobre territorios sometidos y todo ello gracias a la eficacia de la maquinaria militar, cuyo fracaso conlleva el colapso de estados aparentemente bien consolidados. Pero en el caso de Asiria, la debilidad estructural estaba acrecentada por la composición del grupo dominante, un conglomerado de antiguas casas dinásticas y jefes de clanes nómadas, cuyas disensiones pronto se dejarán sentir violentamente. A la muerte de Shamshiadad hacia 1780, todos los territorios ocupados se lanzan a recuperar su independencia, desde Eshnunna a Mari. Comienza así una nueva etapa en la historia del Próximo Oriente.

|

|

Known in the earliest times as Kanesh, the Kültepe ‘höyük’ or mound twenty kilometers east of Kayseri was one of the most powerful kingdoms in the region and the hub of an international trade network some five thousand years ago.

The oldest written documents in Anatolia were unearthed here in the 1800s. Thanks to the deciphering of these texts in Old Assyrian cuneiform and to the excavations, begun in 1948 and continuing today, a wealth of information regarding the Assyrian merchants who founded a trading colony at Kültepe and the everyday life of the region has begun to illuminate the pre-Hittite political makeup of Anatolia.

Archaeological discoveries and excavations in the Middle East acquired momentum at the end of the 19th century. The researchers of that period had a number of different aims, such as acquiring archaeological artifacts of high aesthetic value for Europe’s major museums, determining the geography of the Bible, deciphering the languages of the ancient Near East, and collecting information for political purposes.

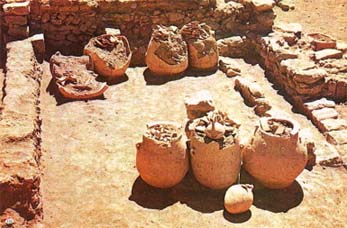

Recipientes de arcilla del karum de Kanish,Turquia

http://www.guide-martine.com/images/kultepe.jpg

They were also the pioneers of the archaeological investigations undertaken in the lands of the Ottoman Empire in those years when so-called ‘Cappadocian tablets’ (clay tablets with cuneiform inscriptions) were frequently sold on the European market for ancient artifacts. Th. G. Pinches, Ernst Chantre, Hugo Winckler and H. Grothe all engaged briefly in excavations at Kültepe to find the source of these tablets, which were known to come from Central Anatolia. But it was the Czech linguist Bedrich Hrozny, a contributor to the deciphering of Hittite, who finally succeeded in unravelling the mystery.

TWENTY THOUSAND TABLETS FOUND

Rumor has it that the villagers were deliberately sending the researchers who came to Kültepe to find the tablets to the upper parts of the mound, whereas the tablets came not from the summit, where the royal palace and other major administrative buildings were located, but rather from the quarter down below where the Assyrian traders had their houses. When Bedrich Hrozny’s driver, in a drunken lapse, happened to let this slip one day, it wasn’t long before Hrozny located some thousand tablets. In 1924 the German Assyriologist Benno Landsberger, who had worked with the tablets sold earlier in Europe, announced that the documents had come from a colony founded in Anatolia by Assyrian traders and that the name of the settlement was ‘Karum-Kanesh’, Karum meaning ‘port’ in Old Assyrian. Since as far back as 3000 BC, each of the Mesopotamian riverbank cities—those on the Euphrates in particular—had been a major port, and all barter, sales and commercial activity in general was carried out here. In time the word ‘karum’ came to mean ‘area of intensive commercial activity’ or ‘market place’.

Scholarly excavations of the Kültepe mound and the Assyrian trading colony in the Lower Town were undertaken by the Turkish Historical Society in 1948. Led by Tahsin Özgüç, a professor of archaeology at the Faculty of Languages, History and Geography of the University of Ankara, these excavations are continuing today. Some twenty thousand clay tablets have been unearthed until now, documenting an important Anatolian kingdom, and a settlement that dates back to the Early Bronze Age and survived right up to the end of the Roman Empire as well as a colony that was the scene of intensive commercial relations between Mesopotamia and Anatolia from 2000 to 1750 BC, and reflecting all the details of their history. Its intensive relations with Mesopotamia had an artistic impact on Kültepe as well, resulting in the production of a wide variety of pottery and seals in particular. The artifacts and tablets found in the Kültepe excavations are exhibited today in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations at Ankara and the Kayseri Archaeological Museum. The most recent and comprehensive book on the subject, ‘Kültepe’, was written by Professor Tahsin Özgüç and published by Yapı Kredi Publications in the summer of 2005.

THE FORERUNNER OF METAL COINAGE

Tin, wool textiles, gold and silver were the products of the long-distance caravan trade carried on by the great merchant families that lived in the Assyrian city-state in Northern Iraq at the beginning of the second millennium BC. Using donkey caravans, the Assyrian traders brought not only tin, which came in all probability from Afghanistan and was extremely valuable because it was found in only a few places in the world, but also luxurious woollen fabrics woven in the various cities of Mesopotamia to the hub of the Assyrian trade network at Kültepe in Anatolia. From here the goods were distributed to Boğazköy and other colonies such as Alişar and Acemhöyük. Although the Assyrians were also engaged in the copper trade in Anatolia, they took only gold and silver back to their own country, these two metals being marks of power among the administrative and elite classes of Mesopotamia, which was very poor in mineral resources.

The goods in question were either traded directly or their equivalents paid in units of silver. Silver, whose weight and value were standardized in small rings or bars, was thus the forerunner of the monetary system that would first emerge in Anatolia some 1300 years later in the Lydian Kingdom. A donkey carried approximately 65 kg of tin and 25 pieces of textiles, and one caravan consisted of around fifteen donkeys. Covering the thousand kilometers from Assyria to Kültepe took six or seven weeks. A caravan, or a large convoy of several caravans setting out together, would either follow the Southern Route, crossing the Euphrates at Birecik to reach Kayseri via Maraş, or choose the Northern Route which proceeded along the banks of the Tigris as far as Diyarbakır and from there via Malatya to Kültepe.

http://www.turkishairlines.com/en-INT/skylife/2005/november/articles/kultepe.aspx

DÓNDE: Capadocia y muchos más lugares(Vázquez Hoys:

Historia Antigua Universal.Próximo Oriente y Egipto, Madrid , Ed.Sanz y Torres, 2007, p.165, sobre los karum en general op.cit.p.163-165.) con bibliografia en p.163, nota 79.

CUÁNDO

h.S.XIX a.C.

CÓMO

Establecimiento de un asentamiento asirio en un lugar alto, fortificado.

POR QUÉ

.Causas: Económicas-Políticas-Culturales-Geográficas-Científicas.

.Consecuencias:-Económicas-políticas-Culturales-Geográficas-Científicas .

PALABRAS-CLAVE

Karum: Centro de comercio asirio en Capadocia (y por extensión, de cualquier país. Muy similares a las actuales Embajadas o Consulados, aunque NO iguales, porque NO ERAN ESTATALES, sino que en el asentamiento había un tribunal asirio para dirimir legalmente problemas entre asirios o de asirios y prehititas ).

Bit-Alim:Casa de los Epónimos (lugar de reunión de los magistrados asirios)

Epónimo:Magistrado que da nombre al año (”En el año en que…era magistrado sucedió tal cosa)…Estos magistrados organizaban el Karum, ponían el capital (no existían monedas AÚN) y ejercían de jueces en nombre del rey de Asiria, muy lejos de su país.

Wabaratum: Agencias secundarias de los karum.

http://openlibrary.org/authors/OL113877A/A._H._Sayce

http://openlibrary.org/works/OL1104502W/The_Hittites

http://www.archive.org/stream/hittitesstoryoff00saycrich#page/6/mode/2up

Archivado en: ACTUALIDAD, ARTÍCULOS, Arqueologia, Arte Antiguo, Costumbres, Cultura clasica, Curiosidades, H. Próximo Oriente, HISTORIA ANTIGUA

Trackback Uri

-

-

There is a critical shortage of infroamtvie articles like this.